Over the last few years, the appearance of DVDs has allowed the works of numerous filmmakers to reach a sizable public. If the name of Jess Franco, for example, has become well known by the American public, it’s essentially thanks to restored editions of his films, which had generated a significant interest toward the filmography of this Spanish director. It would be advantageous that, for once, technology would allow unknown but talented authors to come out of the shadows. Here, I think of names such as José Bénazéraf, Jean-Louis Van Belle, or... Mario Mercier, whose film A Woman Possessed (La Papesse), came out last year on DVD in region 1 of the United States, by Pathfinder/Asterix, in the cadre of a "French Erotic Collection.” If it hadn’t been for a fire a few months later that destroyed the warehouse of the Société d’Édition Les Belles Lettres, the publication of Oeuvres complètes de Mario Mercier (The complete works of Mario Mercier) would have allowed for the complete rediscovery of Mercier begun by the republishing of Journal de Jeanne (Jeanne’s Journal) by Musardine Editions, in 1998.During conversations with numerous amateurs of the fantastique, I have had the occasion of noting at what point the name of Mario Mercier began to reflect a myth, unsolvable questions, and theories sometimes as weird as they are removed from reality. So who is this enigmatic personality of the “fantastique,” author of three films and four novels? In this article, I will attempt to take stock of this striking personality, at once, a novelist, a writer of short stories, filmmaker, essayist, poet, shaman, and visionary painter... An intense personification of the "fantastique", the term that here begs an understanding in a far broader sense, since, with contact with the literary works and films of Mario Mercier, one discovers a “fantastique” considered a mode of life and not just as simple artistic expression.

But who is Mario Mercier? The remarkable journey of this man of multiple talents will give one idea. I no longer remember where I heard his name for the first time. Always being interested in European genre cinema (Italian, Spanish, French, British, or German), I must confess a weakness for the French and Spanish fantastique, two styles unfortunately still unrecognized. Regrettably, French fantastique film in the seventies is not rich in auteurs, the most prolific being without contest, Jean Rollin. To their defense, some filmmakers like Michel Lemoine, Bruno Gantillon or Raphael Delpart attempted to make fantastique films three or four times. Others, like Jean-Francois Davy, Joel Seria or Jean Daniel Verhaeghe each directed only one significant production, making it even more regrettable to amateurs that their brief incursion into this bizarre territory had been so quickly replaced by comedies, documentaries, or other more profitable enterprises that were less risky and, consequently, often less interesting.

Born in 1936, Mario Mercier is mostly known by movie buffs for his full-length films Erotic Witchcraft (La Goulve, 1972) and A Woman Possessed (La Papesse, 1974). These two films were very difficult to find, and still more difficult to view. They were presented in underground theaters in France and Quebec during the seventies. We are able to see this in the reproduced pressbooks, and also in the published reviews of the yearly logbooks of l'Office des Communications Sociales, an organization charged with the evaluation of the artistic value of films presented in Quebec. In these pages, Mario Mercier was no doubt displeased with the type of criticism given to him, as well as that by the specialized French press, which didn’t seem to appreciate his films (see in particular the opinions written in Vampirella on the subject of A Woman Possessed, where it continually received bad reviews).

Mario Mercier steeped himself in the very rich French tradition of writer-filmmakers, such as Fernando Arrabal, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Jean Rollin, or José Larraz. It’s scarcely surprising, in my opinion, as many filmmakers of the European fantastique show inventiveness and an indisputable aesthetic sense- the fruits of a reflection that one can follow traces of in their writings. For example, the understanding of the film work of Jean Rollin resides, to me, in the frequenting of his literary work. There is not one without the other. It is the same with Robbe-Grillet. When I learned that Mario Mercier was a writer, I immediately began inquiring about and trying to obtain his books. This was difficult on all fronts: Two of the books had been censured by the French, one was in a collection of stories by a marginal publishing company, and one book was practically lost. These searches taught me that Mario Mercier had equally published numerous works on reflection, and the spiritual search…

“Concierge in a psychiatric hospital, decorator in a funeral home, painter (of 'the esoteric school' in Nice)”, Mercier carried out a lot of work, in the manner of numerous “popular” writers. His first book, Journal de Jeanne (Jeanne’s Journal), came out in the well-known publications of Eric Losfeld/Le Terrain Vague in 1969. Eric Losfeld was known for being one of the avant-garde editors who, in the manner of Jean-Jacques Pauvert, worked to promote diverse types of literature; startling, and original in different styles (erotica, fantastique, science-fiction, and detective). After all, his slogan was “Eric Losfeld leaves the ordinary knocking on the door.” Eric Losfeld was the first editor to have a French review entirely dedicated to fantastique cinema: Midi-Minuit Fantastique, in which all 24 issues are remembered fondly by amateurs of the fantastique and eroticism. There, they’ve rubbed elbows with prestigious names like Francis Lacassin, Ado Kyrou, Jean Rollin, Alexandro Jodorowsky, Forrest J. Ackerman, and numerous others.

Journal de Jeanne had the effect of a small bomb when it was released and Losfeld was rapidly taken to trial. In his autobiography Endetté comme une mule : Ou La Passion d’éditer, Eric Losfeld wrote:

Journal de Jeanne was the cause of my first big trial, followed by others, even for the books I’ve published previously […]. Mario Mercier arrives one morning. I tell him:I remember with some pleasure the day that I got my hands on this incredible book. Besides the delight of the forbidden, I discovered a universe absolutely tumultuous, but coherent. I recognized right away that I’d never read anything like it in my life. This novel seems to unwind in another world, even though Mario Mercier never says this. It describes the life and adventures of a beautiful young woman, Jeanne, who doesn’t hesitate to assassinate her lovers. She is kidnapped by a sadistic couple that wants to make her their slave, but things don’t happen as planned… The parallel world put in place maintains certain common points with ours, but it also sometimes diverges from it, in particular with regards to the norm. Common denominators with all the beings and the things described include a taste for cruelty and troubled eroticism. If André Pieyre de Mandiargues’ Portrait of an Englishman in his Chateau (Anglais décrit dans le chateau fermé) had been successful, it may have resembled Journal de Jeanne. There are some common points between the two books, which can also be put in comparison to The 120 Days of Sodom (Les 120 Journées de Sodome). A large part of Journal de Jeanne is basically dedicated to the exploration of a universe where one is a prisoner, devoid of any tie with the outside world. Yet this world functions in perfect autonomy, and this is where unthinkable events occur. This fantastique novel follows a peculiar evolution. The first pages, very poetic, establish a unique climate, quickly destroyed by a triggering event: the kidnapping of Jeanne by a depraved couple. From here, Mercier puts aside his refined writing style to adopt one that is choppier and more rapid, at times similar to that of a serial- Mercier is also a fan of serial stories, such as those of Gustave Aimard. But the central idea, which is sometimes imagined in these types of stories, is always derived from an impressive catalog of perversions and sadism.

-You got here just in time; I have the royalty money to pay you.

-But really, Eric, you’ve already had so many problems because of my book; you aren’t going to pay me.

-Listen, it’s done.

I give him a check. He didn’t have a bank account, so it is the type of check that he could only cash at my bank; since it isn’t too far from the office, he returns one hour later, and timidly, he slides an envelope toward me with his hand and tells me:

-Here, don’t open it until after I’m gone.

His copyright was 1,300,000 old francs. He had given me 300,000 francs with one small note: “To pay for the lawsuit.” This is the author who began by refusing his royalties, and then who transferred them to the editor to help pay for a lawsuit, even though it’s one of the risks of the profession. It really was a beautiful moment in an ugly world.There is certainly humor in Mercier’s book, but it is fierce and often bitter. Upon reading, one wonders, if Mercier could get a large enough budget, if a film adaptation would even be possible. Incredible phrases punctuate the story, like: “In the slaughter room, death did not know whether it was coming or going.” (Dans la sale d’abattage, la mort ne savait plus où donner du néant). When the book is again closed, one is left with a strange impression, especially since its ending is as unnerving and unpredictable as the rest of the book. The finale, where M. and J. meet, inspires me to form a rather audacious hypothesis: was this 'M.’ the author, and ‘J.’ his character? What if Jane really existed? I understand then the admiration of Andre Pieyre de Mandiargues before an imagination this unbridled. Mandiargues, a short story writer, novelist, and poet (Goncourt Prize 1967 for his fantastique novel La Marge) wrote this letter to Eric Losfeld shortly after the publication of Jeanne’s Journal:

Dear Eric,In addition, during the trial of Jeanne’s Journal, Claude Gallimard “attached the presiding judge with a stunning and emotionally moving testimony in favor of Mercier’s book […]. The judge told him: “Mr. Gallimard, we know each other and you are honorably recognized […], but finally, Mr. Gallimard, you will not publish this book. And Claude Gallimard, who presumably would not publish Mercier’s book replied, “Sir, which I regret.”Among the books that you have recently sent me, I thank you most particularly for the work of Mario Mercier. I don’t know who this author is, but his invention, in the domain of the fantastique that we love so well, is a prodigious wealth. Insanity, pushed so far towards unrealism, becomes a simple number, which Marcel Jouhandeau named the “algebra of moral values” (algebra de valeurs morales) […]. Without waiting for Mario Mercier to become nationally recognized [at the exposition at the Louvre] I would like you to know that I admire him.

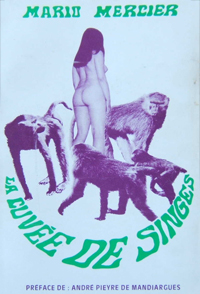

Trials aside, we now find ourselves in 1970. Mario Mercier succeeded once again with La Cuvée de Singes (Éditions Civilisation Nouvelle, 1970), a collection of fantastique short stories prefaced by André Pieyre de Mandiargues. The legitimized novelist confessed immediately to preferring Jeanne’s Journal, which is understandable. The characters in the short stories are more fragmentary; and as such they are unable to deliver the same effect as those belonging to the denser storyline present in a novel. However, one still finds the ‘Mercier stamp’-each new thing is as surprising as the last. There seems to be a darkness extending a spectral shadow over the entire volume; this is not a reading where one is left unscathed. I read Jeanne’s Journal in one sitting, La cuvee de Singes swept me away in the same frenzied, rapid reading. What imagination! The titles of the stories are often intriguing: “Sonia the Dead,” “The X-ray Cemetary,” “The Starlugard Café,” “Hunt of the Wilted Ones,” and “The Little Funfair Test.” And other anticipated titles, which will never be seen, such as “The sun in the mouth” (Éditions Civilisation Nouvelle).

After this collection of short stories, Mario Mercier published The Necrophiliac, with Jerome Martineau, which was completely censored. In this book, Mercier recounts the last days of a necrophiliac who is the prey of his own hallucinations. Between two expeditions to the town on a quest for new prey, he comes upon some dream-like misadventures, like the discovery of a couple in the middle of burying a baby. The ‘new age’ aspect that we see in Mercier’s works in the 70’s is already present, seen in particular the allusion to one of his ideas: that our life on Earth is nothing but a passage through a plane of existence, and Death is nothing but the start of exploration of another plane of existence. This novel, though interesting, is the least original of Mercier’s works. It must be said that the theme had often been addressed, and the realistic predisposition of the author prevents this book from reaching the same level of outrageousness that characterized his first two publications, though one does still find the same esoteric writing and malicious tendencies.

9.In 1972, Mario Mercier was able to direct his first full-length film: La Goulve. However, this wasn’t the author’s first ‘dive’ into cinema, as he had previously directed a short film, Les Dieux en Colère. Referring to the reproduced photo in Midi-Minuit Fantastique (Nov. 1965, last photographic section); we knew absolutely nothing of the film and the still only augmented our curiosity. It is otherwise possible that Mercier had directed other short or medium length films before. La Goulve was produced by Bepi Fontana (Ex-conductor of a Latino orchestra, Bepi Fontana has taken his career path in an unexpected direction: he now directs the online marriage agency ‘Coeur à Coeur”), who, finding the finished product too unmarketable, took it upon himself to add other scenes that changed the nature of the film. Nevertheless, Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs speak of it positively in their own work, Immoral Tales:

"The cast are obvious amateurs and the costumes homemade. At one point the camera pans along a row of witches, posed to reveal their stockinged thighs. One of the girls winks broadly into the lens. For some inexplicable reason the effect is not to dissipate the tension of the scene. It heightens it. We are watching a home move. But one made by someone with very serious intentions. Obsessive. Someone who sees things that he is desperate to show us. At any cost. […] Watching Erotic Witchcraft is like having the top of your skull taken off and blown into. It shakes up your preconceptions about cinema and what it is and should be. Finally you know that you are seeing the world in a new way, through eyes that have a different perspective from the rest of us.”Unsurprisingly, La Goulve wasn't an immense commercial success, though it wasn’t a failure given the modest budget. According to Fontana, it even would have run for 11 weeks exclusively at Saint-Lazare. But Catholic critics cried ‘scandal,’ and the Office Catholique gave it a 5 (not to be seen), calling it “sadistic” (1973, p.271), “ludicrous,” and denouncing the “cruel and erotic scenes.” It was the same story in Quebec: “A ludicrous plot put together in an elementary way with coarse tricks [...]. Vulgar scenes of eroticism" (Recueil des films de 1974, p.86).Next came La Papesse (1974) which the Censure Française banned from the start. In his work, Censure-Moi, Christophe Bier explains: "In 1974, the journalists were talking up a ban on the exportation and exploitation of film, which was seen as an instigator of crime. This affected La Papesse, an esoteric-erotic film, to a great extent [...] whereas The Exorcist was triumphing on the big screen [...]. According to the Commission, La Papesse was “nothing but an uninterrupted succession of scenes of sadism, torture and violence, and a total and permanent disregard for humanity, displayed in a crude and revolting fashion.” On the 27th of August, 1974, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing who recently had become the president of the Republic, during a televised address, promised that films would no longer be censured. The next day, Mario Mercier received a letter from the Minister of Culture requesting that he cut 190 meters out of his film!"

Mario Mercier’s mind was never occupied with thought of censorship. According to Tohill and Tombs, “Again the subject of [La Papesse] is witchcraft, but this time the fictional elements are kept to a minimum. The cast are mostly members of an existing sect and the ‘Papesse’ of the title is a genuine adept- Géziale. La Papesse shows scenes of real possession, secret rites and initiations […] What [Mercier and Jean Rollin] share is a rare ability to visualize those states of existence that are beyond the rational, beyond analysis. For that reason they, like any others who venture into similar terrain, will always run the risk of being not only misunderstood but openly ridiculed- unless they have the safety net of a big budget and ‘artistic’ pretensions to protect themselves with. As Mario Mercier wrote: ‘Death by silence is the fate of all who refuse to follow the safety of the well trodden paths. But whoever dies such a death can always place his hopes in resurrection.’”

As I mentioned earlier, the critics of the time had scarcely recognized La Papesse, and I don’t recall ever having read a single positive review of this title (including in the specialized reviews), except that of Tohill and Tombs. The Catholic critiques this time were entirely indignant: The Catholic Office of French Cinema labeled it as “perverse” and listed it among the films “not to be seen” (Season 1975, p.348). In Quebec, it received the following contemptuous critique: “A hodgepodge of occultism and eroticism […], this film more than satisfies the viewers' and the amateurs’ quota for ugliness. The acting is done at the level of an inept amateur. This film takes the pretext of esoteric practices to compile scenes of sadism and perversion." (Recueil des films de 1975, p.142).

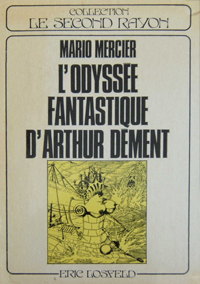

After so many problems, Mario Mercier returned to writing. The final novel characteristic of his first period is L’odyssée fantastique d’Arthur Dément (1976), his second masterpiece after Jeanne’s Journal. Also published by Losfeld, this book recounts the strange adventure of a secret passenger on board a ship navigated through haunted seas carrying a cargo of monsters and other bizarre creatures. Arthur stops in nightmarish lands… notably of the Ile de la Goulve de Ténèbres! He meets strange life forms, such as the Hell Hounds (“de grosses gueules écumeuses animées par l’influx magnétique des orages. Ce sont des matérialisations spatiales de la mort” p. 101) and the Obscurs (“ Les regarder à l’œil nu gèle la vue” p.123). A curious mix of humor, delirium, and pure terror, the book seems to have passed unnoticed. All the more unfortunate, as this commercial failure marked the end of “Fantastiquer Mercier,” who then focused more on books in which the ‘fantastique' was more a mode of life: spirituality, esotericism, personal quest. The first of these books was Chamanismes et Shamans (Belfond, 1977) and was soon followed by Le Monde Magique des rêves (Dangle, 1980).

Chamanisme et Chamans looks at the status of shamans throughout the world, by journeying to these chosen ones and examining their gifts, practices, history, their daily lives, and their powers. The highlight of Chamanismes et Chamans is in the last chapter, which is the narration of a shamanic voyage made by Mercier himself which describes a sort of descent into Hell, made to heal a friend. The author recorded his trip on audio cassette while in his trance among friends. Certain passages are reminiscent of Jeanne’s Journal. Though this was a spectacular finale for the book, this shift is significant of Mercier's change of orientation at the end of the 1970's. From this moment on, the quest towards white (positive) magic replaced the description of the universe as somber and black. Since 1978, Mario Mercier’s works on the spiritual quest are so prolific that it would be impossible to comment on all of them in the space of this article. He continues to write to this day. He has also continued to paint, as seen in an edition of poems by Arthur Rimbaud, published by Albin Michel in 1991, and illustrated by Mario Mercier.

In 1994, Flammarion published the book La France de mutants: voyage au Coeur du Nouvel Age by Jean-Luc Porquet. In this work, an independent journalist attempts to investigate the gurus and adepts of the New Age. One of the chapters (Le Castenada Francais, p. 156-174) is dedicated to Mario Mercier. Porquet, without revealing his identity as a journalist, had actually participated in one of the seminars given by Mercier. His verdict is uncertain: “I have never been so bored during a lecture, but to this day, no other lecture has left me with so many troubling images."

Porquet’s preconceived skepticism may have detracted from the objectivity of his study as he evaluates Mercier as a shaman/guru without taking into account the artist. He particularly accuses Mercier of embarrassing the participants of his lecture, promising miracles that never occur, and abusing the trust of those easily mislead.

Opposite the work of Porquet, one of Mercier's most recent books, La Volupteuse Sagesse de la Chatte Mia (les Belles Lettres, 1997) shows us a man who is less mythical and more like us than the author of Journal d'un Chaman or the enigmatic director of La Goulve. This book reflects on the simple humor and tranquility of a life at the side of his mother and his cat Mia. In this he succeeded in putting his name on a very unique book. We can still see the wacky Mario Mercier, the author of fantastique novels of constant innovation, but the difference this time resides in the fact that this book is devoid of all cruelty. The violence present at all times in Jeanne's Journal and La Cuvée de Singes is absent here. Mercier narrates his first meeting with Mia, and the circumstances leading to her adoption, and then he engages in a dialogue with her. He becomes a comedian with phrases like: "Was there ever a cat-Jesus? Or a Buddhist cat, who would practice compassion for mice?"(p.43). He will even go as far as to invoke his animal familiars, bringing these ghosts to life in the space of a memory.

Mercier’s only other novel to appear after this, Loubia (Atlantis 2000), is more like a disguised attempt at recounting the conversation between a man and a sort of woman-angel. It is clear of all darkness, and anyone reading it in the hopes of renewing a tie with the somber phantasmagoria of his first writings will be disappointed…

Visiting Paris in 1999, I nevertheless was able to schedule a meeting with Mario Mercier, in the company of my good friend Pascal Francaix- a huge fan of 'B' cinema, the author of Jean Rollin, Cinéaste Écrivain (Édition Films ABC, 2002), and of many fantastique novels. Mercier chose the Café de Flore for our rendezvous, and we told ourselves that he would probably arrive late. Actually, we waited 45 minutes, scrutinizing each new arrival while trying to discern if he acted like Mario Mercier. From time to time, I would dare to go and ask "Are you Mario Mercier?" and each time I was given a funny look. However, when he arrived, Francaix and I knew right away that it was he. Dressed simply, he carried a backpack which contained some soil from his native land, which he made us smell. You can imagine our surprise, even if we expected some peculiarities from Mercier.

He was so kind as to have brought with him a copy of La Cuvée des Singes, of which he seemed to be (wrongly) ashamed, in saying, “This is an old scatological thing that I wrote some time ago.” Despite the cold indifference of the waiter at the Café de Flore (who even refused to take our picture!), the conversation livened up little by little. Mercier revealed that he had always been passionate about the fantastique, and he confessed that he still has numerous unedited novels at his home. He spoke of a terrifying novel that he had just begun to read, the title of which I have (alas!) forgotten. He’s looking for a publisher. Some negotiations have started with Pocket for republishing Arthur Dément, which would begin a new series of adventures for that character. However, Mercier and the director of Pocket, Jaques Goimard have been unable to come to an agreement. The only copy of Arthur Dément that Mercer had was stolen…! Without this version of the book, nothing seems possible. I had forgotten to mention that with the help of the French National Library, the problem might be fixed. Les Belles Lettres was perhaps interested: the director Michel Desgranges is an admirer of both Mercier and Jean Rollin (the two are very good friends), and he published the latest of Mercier's books. Mercier handed us a flier for his seminar on “personal development” which he greatly encouraged. Francaix and I didn’t comment on that much, as we aren’t interested in such things, to say the least. To be honest, the participation fee was very high. As an oracle, Mercier sometimes made some surprising statements: “You are hungry for freedom”; “You neglect your relationship with the Sea”…when we tried to ask about La Goulve, the auteur-filmmaker squarely refused to speak of it. Pete Tombs warned me! Mercier never forgave Bepi Fontana for having distorted his film... and Tombs, who had recently found a version of the film in 35mm couldn't release it on DVD for this exact reason.

What of La Papesse then? La Papesse, for Mercier is another story of grand deception: a film killed by the censure and the distributors, released at the worst possible time. The Exorcist had taken away from his film, and viewing was restricted so as not to take attention away from Friedkin's film. Twenty-five years later, however, memories aren't quite as precise. I would have liked to speak of Géziale, to know what ‘La Papesse' had become and who she was, but Mercier never responded to those questions and instead wanted to know what we had done. Francaix and I did want to talk a bit about our own work, but our own careers as novelists seemed of little interest in comparison to what Mario Mercier could tell us. We learned among other things that Mercier had grown up in a house "more or less haunted," and there was brief talk of eroticism. Mercier likes, he said, an "érotisme à la Kubrick"; an allusion, I assume, to the film Eyes Wide Shut, in theaters at the time of our interview.

We spoke a little of Eric Losfeld… and Mario confessed to feeling saddened upon reading that he was "but a man of a single book" in the biography of the author of Terrain Vague. For good reason... Finally, at the end of our hour long interview, we still didn't know much on Mercier. It was difficult to keep our discussion along a precise direction, and the situation didn't lend itself well to note-taking. However, we promised to keep in touch, and I told myself that for now, simply the interview would do. A few months later, Mercier contacted Francaix about publishing Arthur Dément. Francaix sent a few words to Jaques Chambon, who doesn’t like Mercier's work much. In my opinion, the ideal situation would be for it to be included in the new collection headed by Jean Rollin for E-dite. More to follow...

Since then, Mercier published a play called On nén finit pas de fair la Guerre (Éditions du Cosmogone, 2002). Even though he promised to respond to my letters, I’ve not gotten any responses, except for a friendly postcard in 2001. Nevertheless, if I ever return to Paris, I will try to contact him…Until then, La Papesse will allow international fans the opportunity to know Mercier’s work, and the republishing of Jeanne’s Journal, always available at used bookstores, will allow readers the chance to discover a very talented writer, who we still hope will speak to us, in our preferred domain…

Original article by Frédérick Durand,

Translated by Mandy Hoff