Eiichi Yamamoto, 1973

Runtime: XX min.

Format: Japanese DVD

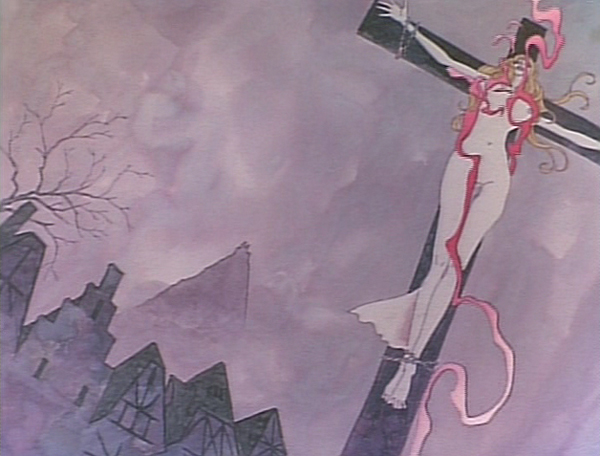

It becomes apparent early on when viewing Belladonna of Sadness (Kanashimi No Beradona) that this film is quite unique. Certainly the first, and possibly the only animated film that might be classified in the pinku genre. But even though the film is supposedly animated, nothing seems to be moving at first. You instead see a series of elegantly designed still drawings depicting a harmonious wedding between a peasant couple in 14th century France, as a woman sings her narration in the soulful style of a 70s rock opera. This is the film's only joyous scene, as moments later the new groom is pleading with the local land baron to reduce the marriage tax he can't afford. The baron instead decides to exercise his "droit de seigneur" with the bride. It is here, several minutes into the film, that full animation is finally used, in order to depict the rape of the virgin bride with metaphorical imagery much more disturbing than what a literal depiction of the same events could provide. A sign of things to come, as this is only the first in a series of tragic events that push this woman, through desperation, into the world of witchcraft.

Belladonna of Sadness is the product of an animation studio that knew it was doomed, and it shows. Osamu Tezuka's Mushi Productions, which had been so successful producing TV series like "Astroboy" and "Kimba" in the 60s, was faltering badly in the early 70s for a variety of reasons related to the oil crisis and Japan's economy in general. But in actuality, Mushi Pro's first venture into feature animation, 1969's 1001 Nights, had been successful enough to spawn a second film in 1970, Cleopatra. Tezuka, always a trailblazer, had decided that Mushi Pro's feature films would be made to appeal to adult audiences so as to expand the potential for animation as a film medium (whether these first two films succeeded in that regard is debatable). But even though these two features did relatively well at the Japanese box office, the economy was beginning to take a toll on Mushi Pro, and Tezuka refused to downsize. When Tezuka left the studio in 1971 to focus on manga, the remaining employees must have known they were on the road to bankruptcy. A filmmaker has two choices in a situation like this: cut your losses and go out with a whimper, or pour all your remaining resources and effort into one final, revolutionary labor of love. The folks at Mushi Pro chose the latter option and Belladonna is the result. Predictably, the film had a dreadful theatrical run of only 10 days and Mushi Pro went bankrupt within a few months.

Belladonna is an adaptation of La Sorcière, the 1862 novelized history of satanism and witchcraft in the late middle ages. The book was written by feminist, freethinker, and Frenchman Jules Michelet, who, like many other post-revolution French intellectuals, was eager to condemn the barbaric European forces of the prior few centuries. In Michelet's story, the practice of witchcraft is not simply the leftover trace of ancient pagan traditions, but an active rebellion against an oppressive church and system of government. While the church expected serfs to suffer and slave away during their time on earth with only the promise of a better afterlife to console them, witchcraft provided a glimpse of happiness in the here and now. Where the church feared the imperfections of nature, witchcraft embraced them. Where the church could only respond to ailments with prayer and holy water, witchcraft offered painkillers and psychoactive potions from datura plants. According to Michelet, the spirit of rebellion and experimentation found in 14th century witchcraft was a progenitor of the enlightenment values yet to come. Furthermore, this was a movement led by women, those who likely suffered the most at the hands of the church and the feudal system. He insinuates that society's emancipation from oppression is contingent on female liberation and sexual empowerment. It's easy to imagine how these ideas must have resonated with the revolutionary leftist Japanese filmmakers of more than a century later (yes, they were working in animation too).

The film adaptation of La Sorcière is often very faithful to the book, to the point of replicating much of its dialogue. It tells the story of an archetypal witch (unnamed in the book, named Jeanne in the movie) who suffers a series of misfortunes that lead her down the path from being a chaste, obedient peasant's wife, to giving in to her awakened earthly desires, to finally blossoming into the bride of Satan himself. The process of selling one's soul to the Devil can be interpreted literally or metaphorically, but keep in mind that at least according to Michelet, those who would enter into such a pact in the middle ages presumably believed they were literally sacrificing eternity for just a glimmer of relief from a cruel and bleak life. A pact with Satan was the ultimate act of desperation, not just a casual mistake. On the other hand, none of the "powers" that Jeanne acquires from the Devil require any sort of supernatural explanation. They are simply things that Medieval society has withheld from her: an independent spirit, a liberated sexual libido, communion with nature, an inquisitiveness that allows her to discover the medicinal properties of plants, an air of confidence that enhances her powers of persuasion. Her relationship with the Devil may be nothing but a psychological coping mechanism for the brutality she suffers.

The content of Belladonna's story was radically different from any other animated feature up to that point, Japanese or otherwise (Ralph Bakshi included), but its method of storytelling was just as radical. The film was designed by illustrator Kuni Fukai, whose drawings may appear to be more Western than Japanese. But his style seems to be a sort of late 60's psychedelic Art Nouveau revivalism inspired by the likes of Aubrey Beardsley's Victorian parodies, which were likewise inspired by erotic-grotesque shunga prints, thus coming full circle back to Japan. Much of the film features Fukai's drawings directly, with the camera panning over still frames, but the film often transitions seamlessly into full animation thanks to animation director Gisaburo Sugii. This extra motion tends to happen during the film's numerous sex scenes, but they are generally not visually explicit. Instead, they are animated in a variety of highly stylized expressionistic ways, taking full advantage of animation's ability to caricature form and motion. Because of the film's aesthetic appearance and radical themes, it sometimes appears to be very much a product of its time--the early 70's--which is either good or bad depending on who you ask (the biggest giveaway is its great psychedelic rock / jazz fusion soundtrack which is occasionally reminiscent of J. A. Seazer). But it's important to remember that it is based on source material from over a century before, and that there really are no other comparable movies from that period that would justify an implication that it's at all derivative.

Japanese animation was still in its prolonged adolescence in 1973 (you could argue that it still is today). It was only five years earlier that adult political and social themes had begun to make an appearance in anime with Horus, Prince of the Sun. There had not been much experimentation with form or design aside from Tezuka's own independent shorts. So when an experimental arthouse animated feature like Belladonna was thrust onto Japanese audiences, it was such a drastic departure from convention that nobody seemed to know what to make of it. It ended up disappearing into obscurity and not really influencing anybody in the anime industry (at least not until recently, as it's being slowly rediscovered). It's closest-related cousin is probably Hiroshi Harada's adaptation of ero-guro manga artist Suehiro Maruo's Midori, similar both for its technique of alternating short scenes of full animation with a "slideshow" of still images, and also for its story of unrelenting cruelty. The film probably has more in common with films from the likes of Koji Wakamatsu than it does with other anime. Granted, it certainly took longer to make and cost a bit more than a typical pinku film (though it's clearly a low-budget flick), but like many of the best films in that genre, Belladonna manages to promote some form of feminist ideology while simultaneously exploiting the entertainment value of crass misogyny.

Joshua Smith, 2008

Joshua Smith, 2008

Promotional Poster