Runtime: 100 min.

Format: Kino DVD

I've lost any conception of what it is exactly that makes a movie perfect for me. I once thought it was a primary aesthetic reaction: a culmination of images and music, with some sort of hyperbolic, mimetic emotionality. A sense of poetry-- but not the poetry of the Romantics, or anything hegemonically beautiful, rather, a poetry of violence, excess, of desperation--all contained within a narrative.

But then I discovered the world of experimental cinema and video art. In video art, aesthetics are eschewed in favor of the immediacy that the medium of video offers. There is nothing beautiful to look at, and sound is often terribly muffled, recorded in camera. But that's not what video art is about, video art is about a concept, it's about an idea. Vito Acconci was not a filmmaker, he was a conceptual artist who occasionally happened to work with a video camera. So do we dismiss this from our understanding of "motion pictures" ? Just because the medium of moving images is used in a different way, this shouldn't exclude an entire genre. It's different, and it forces the viewer to reconsider his conception of what a "movie" is. Experimental cinema does this as well: often an experimental film is more about structure (or once again concept). Narrative is almost consistently overlooked (at least in most well known examples: Michael Snow, Stan Brakhage, etc.). We are now, thanks to Greenbergian modernism, looking at the material qualities of film itself. But some of what was originally contained in perfection shines through. Paul Sharits' repetition and strobing seems awful and obnoxious at first, but further reflection reveals there is a poetry of violence and excess there, and, in a roundabout way, a definite sense of hyperbolic emotionality. The images, though not images you would expect to find in a film, turn out to be beautiful too.

So where does that leave me now? I'm not sure. There is one thing that I am sure of though. Seven years ago I watched the Quay brother's first feature length film, Institute Benjamenta at 5AM before I headed off to a day of my Junior year of high school. I thought it was perfect then. Last night, seeing the film for probably the 10th time, I still think it is.

Has nothing changed? I know that I view film now in an entirely different manner from when I first saw the film. My criteria for what works and what doesn't work is completely different. I don't think I suffer any sort of sentimental attachment to the film either, as I've specifically tried to avoid that throughout multiple viewings: I've never let myself tie the film to a particular part of my life. I know there was something special, exciting about the first time (the first time is always different), but repeated viewings have just shown the film to be better, something new, something better.

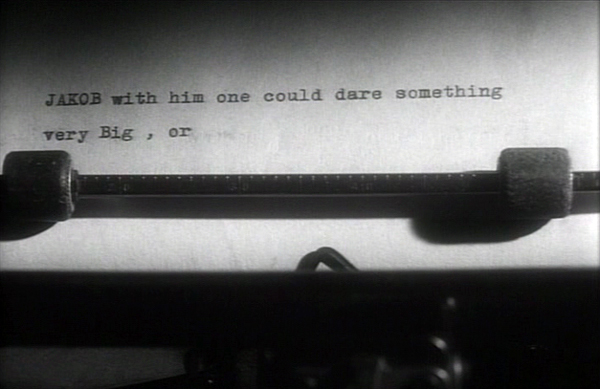

When I first saw the film, it was a dream that I wanted to escape in. The film works best when paying careful attention to it's construction of atmosphere. It's oppressive, but in a stunning way. Every single line that Alice Krige mutters as Fraulein Benjamenta is labored, forced out, like she is not sure she should even be speaking, but must. There is a immediacy in her vocal intonation that makes her dialog seem present. Mark Rylance, as Jakob, is completely outside of the film the whole time, which is why Fraulein and Herr Benjamenta gravitate to him, "JAKOB with him one could dare something very Big." He is the clown at the funeral of meaning that the Institute claims to offer.

The set design of the film is what initially made the film so magical to me. The antiquated deer/stag parts decorating every mysterious corridor and doorway, the hyper present texture that everything takes on-- all of this lensed through Nic Knowland's (who got his start shooting John Lennon and Yoko Ono's experimental films) utterly brilliant cinematography, recalling, in a more textured manner, the brilliance of Sascha Vierny.

...

There is an awkward tension throughout the film: Jakob's voice over narration often betrays what is happening on screen. We are told that "the inner chambers contain nothing but a goldfish," while our eyes have already been privy to an entire subterranean level, accessed through awkward doorways located in the center of walls, sometimes created by drawing a concentric circle on a blackboard and walking through it while blindfolded. I don't think that the film suggests that Jakob's imagination is running wild under the domain of repression, rather, I think the world is far more mysterious than Jakob is willing to accept.

A dynamic tension is also constructed via the subversion of narrative. Ostensibly, Institute Benjamenta does have a classical narrative structure: the film begins with Jakob arriving at the institute, the climax occurs with the death of Fraulein Benjamenta, and denoument comes with Jakob and Herr Benjamenta leaving the Institute in the snow. However, these three events are only coincidentally related. The arrival of Jakob does not lead to Fraulein Benjamenta's death (she was already virtually dead), nor does the death lead to the end of the institute (Herr Benjamenta tells Jakob he has closed the institute before). It is arguable that the arrival of Jakob leads to the closure of the institute, but reducing the narrative to an "A, then B" structure is reductive, within the context of the larger film.

As I reach this point, I realize once again that I still don't really know what I'm aiming at here. I suppose, really, that what I'm trying to say, to clarify, is that this is a good film. An amazing one.

Mike Kitchell, 2008

Mike Kitchell, 2008