Runtime: ~40 min.

Format: Fantoma DVD

Lucifer Rising exists as an intersection between two filmic ideas, and it is within this intersection that the film gains it's power: more than any other film, Kenneth Anger's Lucifer Rising is about spectacle and hypnosis.

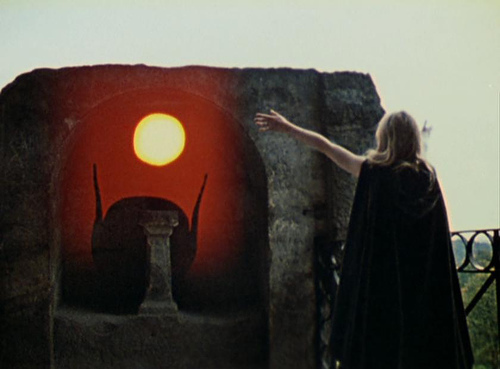

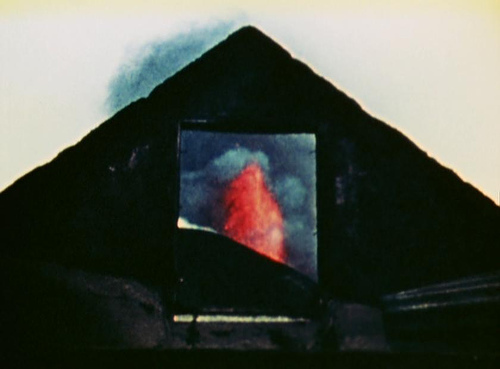

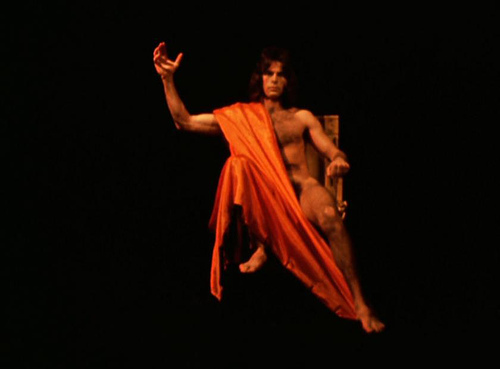

From a level of spectacle the film is pure ritual, literally and figuratively. Juxtaposing mythological images of ancient Egyptian Gods with contemporary Thelemites, Anger delineates the progressive nature of time in order to present to the spectator the necessary elements of the ritualistic form his film is taking. But what makes the ritual appealing to the audience is divorced from this esotericism--it's the nature of the films' aesthetics. Anger's level of artifice is exemplary; hyper-pervasive primary colors permeate every frame, shockingly electrified negative images pop up for brief moments, highlighting both the phenomenon of nature (lightning, volcanic eruptions, the birth of an alligator/lizard) and the exclamation points of banal events (as we tour through the hallway a man absently shuffling a deck of cards suddenly throws them into the air).

Anger's camera--generally static at a fixed angle in all of his films leading up to this one--finally begins to move in the aforementioned hallway scene, which is one of the most enigmatic tracking scenes that I've encountered through all of cinema. As we move through Anger's many tableau with a steady tempo, echoed by the calm score, there is an abject atmosphere of anxiety that arises: the film is telling us that something is going to happen soon, and we don't know what that is, but it's going to be something important.

Bobby Beausoleil's score is another necessary element of the film: composed from his prison cell, Beausoleil's score provides the soundtrack for Anger's film in the only instance where specific music has been produced for the specific film (excluding Jagger's grating drone "composed" for Invocation of My Demon Brother, the rest of Anger's films, as popularly recognized, are simply coupled with 50s and 60s pop music, often to an ironic extent-- there is no irony present in Beausoleil's score for this film). The soundtrack itself is an excellent piece of work, with or without Anger's images married to it. It is a bit psychedelic and ambient, echoing both the naturalistic evocations brought about by Anger's pensive landscape shots, and the internal psychedelia that plays a pivotal role in the film.

Beausoleil's score also plays a major role in elevating the level of hypnosis present in the film; the pulsing score with it's utter repetition and subtle progressive changes feeds directly into the subconscious, the same way Anger's images work their way through cracks. In The Poetic of Cinema, Raoul Ruiz discusses the idea of hypnotic film in his chapter on Shamanic cinema (a more than apt term for Anger's films, to be sure). He sets forth the idea that when a film has an hypnotic element, the viewer may fall asleep. This is not the result of boredom, in fact this opens up, rather, an expanded film for the viewer: the dream world and the film world begin to mesh into a single unity, allowing the viewer to become an alchemist, colliding the "reality" of the film with the subconscious connections the mind brings forth. Being a Thelemite and follower of Crowley himself, an often ignored part of Anger's cinema is the fact that all of his films are "intended as [...] magickal working[s] on the viewer," with Lucifer Rising intending to open "up a wider field of the sublime effects of nature and ancient history" (which relates to the earlier mentioned delineation of past and "present").1

Anger's magick remains esoteric, unknowable to the viewer. But one thing that can be read without occult historical knowledge is the simple repetitions and geometric shapes that pop up repeatedly throughout the film. The aforementioned hallway tracking scene demands attention, and that attention is shattered, popped, at certain moments. There is a level of control that the image has over the viewer. Same with the stoic profiles of the Gods in ancient Egypt; the camera demands attention, and despite what could ostensibly be classified as camp costuming, these images attain a significant importance. Whereas Jess Franco using languid tracking shots and repetition for the purpose of an extension of sexual ennui, Anger uses the same techniques for the purpose of hypnosis. It is, however, worth noting that both Franco's sexual ennui and Anger's techniques of hypnosis have an aim of ensnarement, a goal of pulling the voyeur/spectator into the diegetic world of the film.

The only problem with the film is that from what people expect of Anger (from a locus of popular culture), Lucifer Rising is more of less at odds with what has generated Anger's reputation: it, to a large extent, lacks the hyper structural editing that initially put Anger on the map, as well as being totally devoid of the pop music that Anger pioneered the music video with. It is also not necessarily indicative of the homosexual avant-garde that Anger often gets lumped in with. The often ridiculed "campy" costumes are merely ritualistic signifiers. They are just conduits to a larger idea that is inherent within a much larger system, and reading the images as nothing beyond camp is discredited Anger as an artist, as a magician. But these are all surface level details-- further exploration into Anger's oeuvre reveals that Lucifer Rising is more accurately a culmination of everything Anger learned in making films. The obsessive fetishism of objects and sensory details is present, as is the already mentioned religious strain that permeates all of Anger's films, and all of this makes it easy to see that this is Anger's best film.

1 Moonchild: The Films of Kenneth Anger, edited by Jack Hunter

Mike Kitchell, 2008